Most

of us are familiar with the story of Florence Nightingale. The heroine of

hundreds of primary school history lessons, her valiant efforts to clean up

hospitals in the Crimean War saved thousands of soldiers' lives, and changed

nursing forever, with its focus on caring and cleanliness. After the war was

over, she returned to Britain, and dedicated the rest of her long life to

improving standards in nursing and hospital cleanliness, including submitting

radical new designs for hospitals to improve the care of the sick.

Seen here in totally accurate drawing definitely made at the time

But

for all her good works, Florence Nightingale has a problem, which makes her a

terrible choice of name for these new NHS hospitals. The Crimean War took place

from 1853-1856. At this point, the commonly accepted theory for the cause of

disease was the miasma theory- this stated that disease was transmitted through

'bad air,' caused by the rotting or decay of material. This was central to

Florence Nightingale's thinking: when she ordered the hospital wards cleaned,

and the buildings totally redesigned to allow for more air and light, it was

miasma she was trying to combat.

Yet

scientists had also noticed something interesting. When this rotting material

was looked at through microscopes, it was seen to contain thousands of

micro-organisms. The explanation of this was that these 'germs' were caused by spontaneous

generation- the breakdown of rotting material, which caused illness, also

caused the micro-organisms to appear from nothing. They had all the right

answers, but not the right order.

Suspicions

had persisted for years that this was not quite right. Some medical practitioners

were inching towards the solution. In the 1790s, a Gloucestershire physician

Edward Jenner had realised that giving someone cowpox stopped the far deadlier

smallpox. But he was totally unable to explain how this fantastical discovery

actually worked. In the 1840s, a Hungarian doctor called Ignaz Semmelweis,

trying to solve the problem of women dying from childbed fever, saw that his

friend also perished from the same disease when he cut himself during an

autopsy. Semmelweis concluded that somehow, doctors were carrying the fever

from the autopsy into the delivery room. He immediately insisted all doctors

wash their hands, and the infection rate tumbled. But lacking proof as to why

his ideas worked, he was hounded out of a job, dying in an asylum, ironically

of blood poisoning. In Britain, an outbreak of cholera in 1854 in Soho was

stopped by the diligent work of Dr John Snow, who traced cases and realised

that they were all connected to the same water pump. When Snow inspected the

pump, it transpired it had a leak from a nearby cess pit. Snow concluded that,

somehow, cholera was spread through the water. In their own way, each was

inching towards the solution of human disease. But they weren't quite there.

The

answer to the greatest scientific mystery of all time came from a French

research chemist. Louis Pasteur had been asked by a friend to investigate why

the beer and wine in his brewery kept going off. Pasteur noticed that, the

greater the concentration of micro-organisms in the liquids, the more rotten it

had become. Boiling the liquid killed the micro-organisms, and so stopped it

from going off. Pasteur suggested this would also work for human illnesses. He

called this the germ theory. In 1880, he had the final piece of the puzzle,

when his assistant unknowingly exposed a chicken to weak cholera. When they

tried to give the chicken full blown cholera, it was immune. The secret of

Jenner's vaccine was at last cracked open.

Many

in the medical community reacted with scorn. Pasteur was a chemist, not a

doctor. And how could such lowly microbes fell something so complex as a human

being? One pamphleteer said:

The disease-germ-fetish, and the

witchcraft-fetish, are the produce of the same mental condition; both of them

considered simply as superstitions, or harmless theories.

The

author? Florence Nightingale.

In

her defence, she did change her tune. By the time she conducted later campaigns

to improve sanitation in India, she was advocating handwashing to kill germs.

And her ideas for cleaning hospitals to remove the miasma did work against

germs, albeit totally coincidentally. But it does all make her a curious choice

to be the poster of the new NHS hospitals set up to fight the worst outbreak of

disease in a generation.

Far

more fitting would be for the NHS to honour the real disease trailblazers,

either who advocated germ theory before Pasteur, or who took his ideas and ran

with them:

- Edward Jenner- Developed the smallpox vaccine in the 1790s, setting us on a path which ended with smallpox being the only disease eradicated from humans.

- Ignaz Semmelweis- The John the Baptist of germ theory, crying (and ignored) in the wilderness that disease was carried on the hands of doctors.

The other doctors resented these changes so much they forced Semmelweis into an asylum

- John Snow- The doctor who solved the mystery of cholera transmission in the 1850s.

The map that Snow used to plot the cholera cases- the infected pump was at the centre

- Joseph Lister- A surgeon who transferred Pasteur's work into the operating theatre, inventing antiseptics and ending one of the biggest dangers of pre-modern surgery.

Carbolic acid being sprayed in the operating theatre by Lister- inelegant, but effective

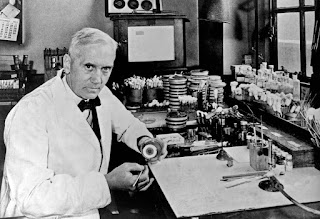

- Alexander Fleming- Accidental discoverer of penicillin, the first medicine which could kill multiple micro-organisms.

Fleming holding the penicillin discovery, presumably about to file it away for a decade (no, really)

- Howard Florey and Ernest Chain- Found Fleming's original (and ignored) research on penicillin, and turned it from a lucky accident in the lab into something which could, and did, save billions of lives.

Florey and Chain, busy doing what Fleming should have done ten years previously and actually making more penicillin

But

then again, maybe choosing someone who was right, albeit by accident, and who steadfastly

refused to change their ideas until it was long past the time to do so, is the

best summary of Britain in the coronavirus outbreak.

No comments:

Post a Comment