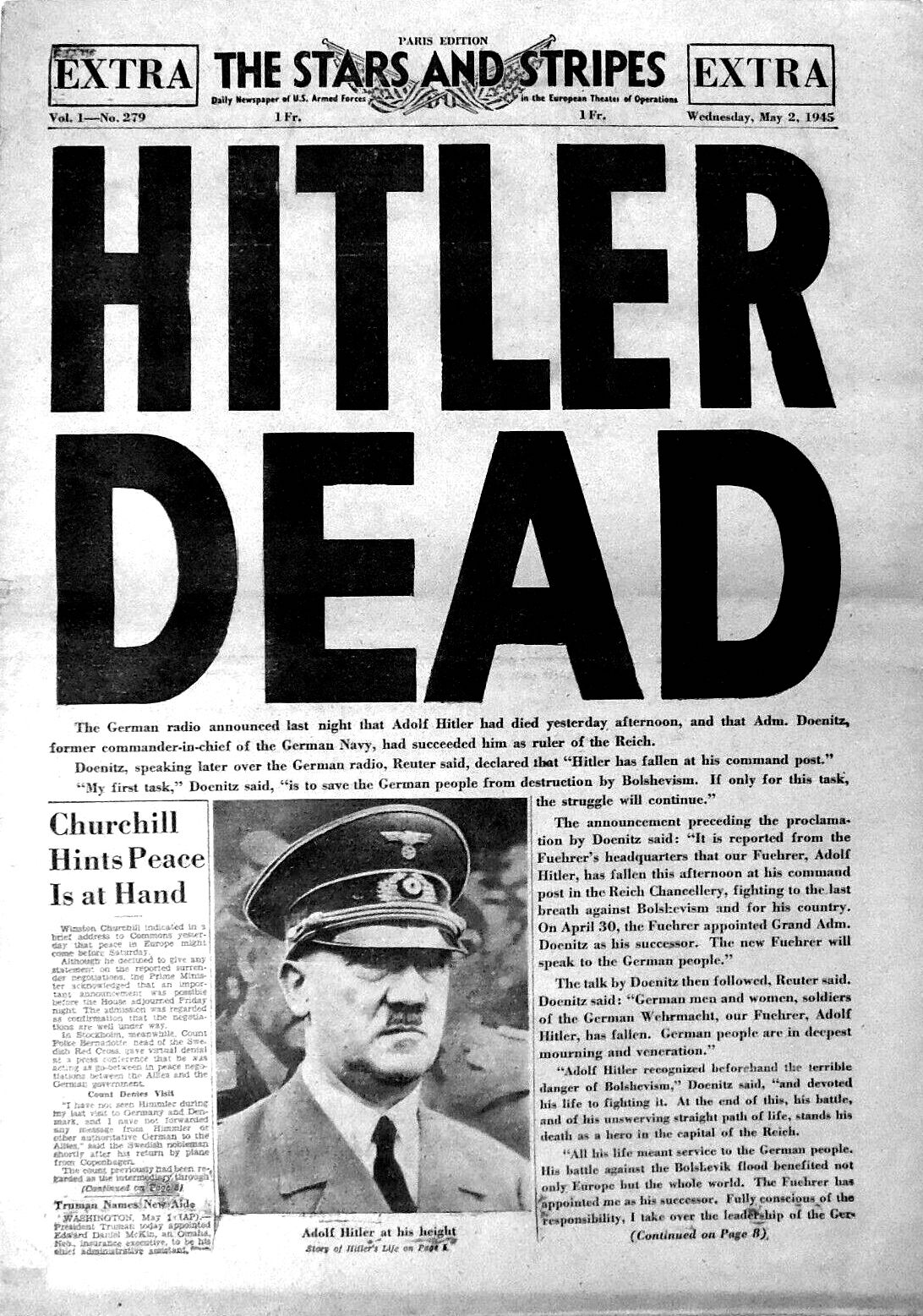

Then, on 1st May 1945, Hamburg radio began broadcasting a newsflash. Adolf Hitler, the Fuhrer of Germany, the man who embodied the Nazi party and state, was dead. He had actually been dead since the previous afternoon. After dictating his last will and testament, Hitler had committed suicide, along with his new wife, Eva Braun. Their bodies had been burnt in the garden of the Reich Chancellery. The man often identified as the epitome of evil in history was no more.

The news everyone had been waiting for- but the war was not yet over

Yet for ten days, the Third Reich fought on. Nazi Germany was a state built around 'ein volk, ein reich, ein fuhrer,' but somehow it staggered on without its supreme leader, or for that matter many people or much of an empire.

In the days running up to Hitler's demise, the struggle to succeed him had raged inside the Nazi machine. Hermann Goering, Hitler’s designated successor, had telegrammed Hitler on April 23rd asking for permission to assume power, in effect trying to remove the besieged leader. Five days later, the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, was revealed to have approached the Swedish government to act as a peace broker between Germany and the Western Allies. Outraged, Hitler sacked both Goering and Himmler, declaring both to be traitors. In his last will and testament, Hitler ended the office of Fuhrer, dividing it back into the Chancellorship and the Presidency, which had been the situation during the first year and a bit of Hitler's rule, when President Hindenburg was still alive. It was to another military leader that Hitler turned; Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz, the leader of the German navy, would become President, and Joseph Goebbels, the director of propaganda, would become Chancellor.

Goebbels’ Chancellorship lasted a little under 24 hours, before he too committed suicide in the Fuhrerbunker in Berlin, along with his wife; they also murdered their six children. This left Doenitz as the last Nazi standing. From his headquarters at Flensburg, he became the President of the German Reich and the commander of the armed forces.

The new leader of Nazi Germany, Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz

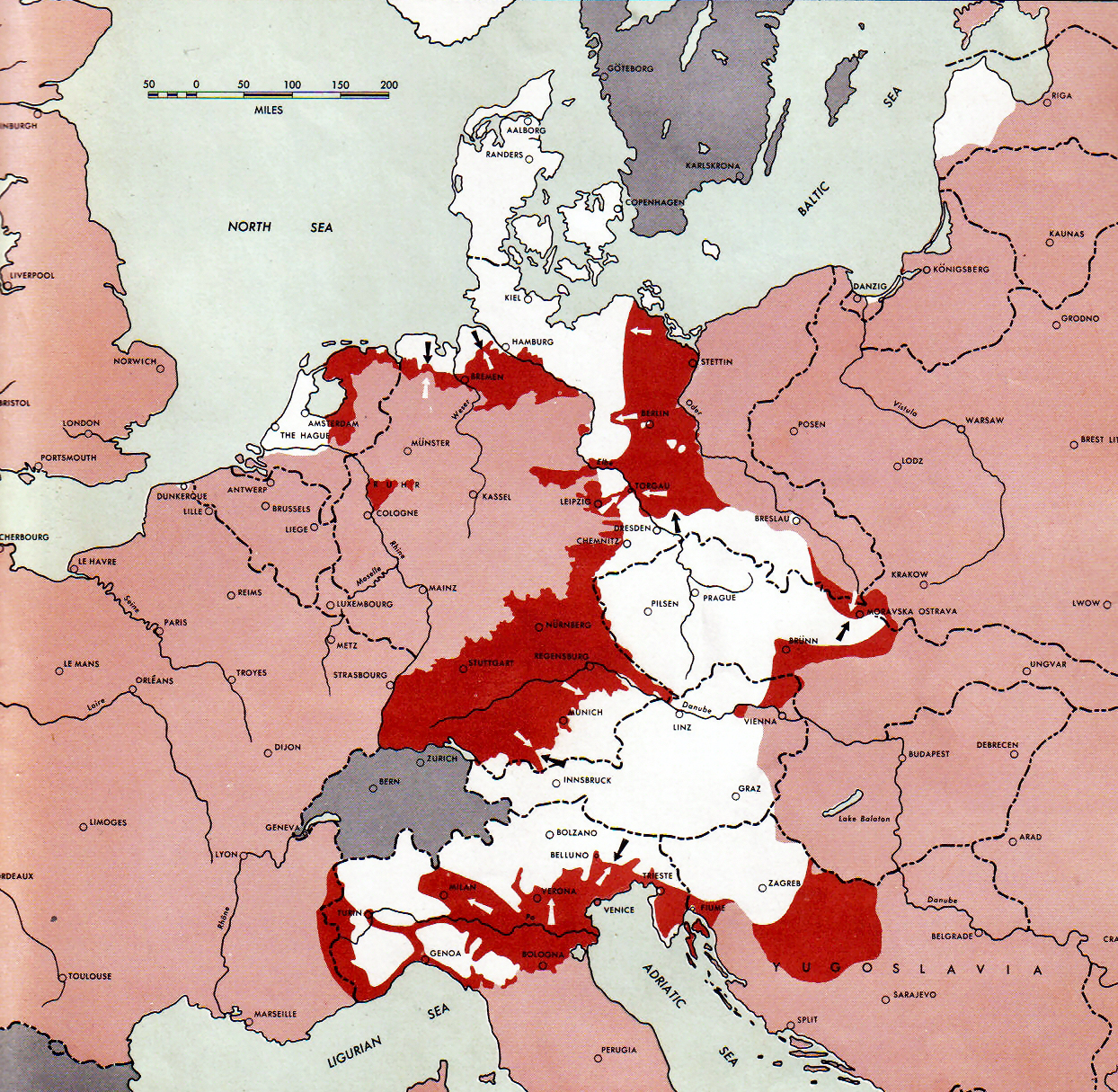

At

the time of Hitler's death, the white bits were the extent of Nazi

control; being Fuhrer wasn't as attractive a job prospect by this

point...

Not because he expected to win. Rather, Doenitz's policy was to hold off the Soviets for as long as possible, while entering into localised negotiations with Western Allied commanders. The hope was that conducting separate peaces would make the Western Allies fall out with the USSR, and they could then unite with the Germans in an anti-Communist crusade. In case this fantasy didn't work out, Doenitz's other objective was to surrender as many soldiers to the West as possible; the savagery of Wehrmacht atrocities in the USSR meant that there would be no quarter given by the Soviets, even in defeat.

This also explains Doenitz's decision to exclude prominent Nazis from his government. Apart from Albert Speer, none of the new ministers had been notable in the Nazi government so far. The SS and other organs of the Nazi party were kept at arm’s length. The idea was to present a new face, one which the Western Allies could do business with.

The changes were only cosmetic. The Hitler salute and greeting continued, a bust of Hitler remained in Doenitz's office, and the Nazi party remained in existence. The Nazi system of summary justice carried on, and around 10,000 concentration camp prisoners remained in the hands of the SS. This was business as usual.

It even looked as if the plan would partially succeed. Doenitz's representatives met the British general Bernard Montgomery, and offered to surrender all Wehrmacht forces in north-west Germany to him. Montgomery refused to accept that, but did hint he would accept the surrender of any forces fleeing the Eastern Front. The deal eventually hammered out with Montgomery and Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, was that on 5th May, all German forces in north-west Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands would surrender to Britain and America. On 6th May, all German forces in Bavaria and the south west would surrender to the Americans. Doenitz also began talking to the US General George Patton, whose forces were racing through Czechoslovakia. The idea was to surrender German forces fighting on the Eastern front to Patton, and enable him to enter Prague. Patton was famously anti-communist, and the USSR had already been promised control over Czechoslovakia at the Yalta Conference. He had been approached deliberately to cause maximum rage in Moscow.

Montgomery has a reputation for being prepared to play the media game. This time, he didn't play it well enough. He failed to put out a version of the surrender order. Doenitz and the Germans spotted this gap and published their own interpretations of what had been agreed. As well as disagreeing over warships and areas to be surrendered, it described the agreement as a truce, not a surrender. A pause in the fighting, not an end to the fighting. It looked to all the world as if Britain and America were conducting talks with the Nazis and excluding the Soviets.

Montgomery accepting the partial German surrender at Luneburg Heath; this act caused chaos amongst the Allied leadership

Too late, Eisenhower spotted the trap. He forbade any further partial surrenders like this. Patton in particular was ordered to halt his advance into Czechoslovakia, despite howls of anguish from Patton at not being able to support the Czechoslovak resistance battling for control of Prague. In Moscow, Stalin was livid. Could it really be that, at this 11th hour, the West was going to betray him? Would they soon be joining with the Nazi remnant for a new war against communism?

When German representatives went to Reims in France to try and surrender wholesale to the Western Allies, Eisenhower was ready for them. He refused point blank to accept any surrender that did not include the USSR. Doenitz told his representatives to stall, to give him time to pull as many forces and refugees away from the Red Army and into the arms of the West. When this became obvious, Eisenhower told the Germans he would close the Western Front to new arrivals, and fire on anyone trying to cross. This would leave the Wehrmacht trapped between the Western Allies and the Red Army, with no alternative but slaughter. When Doenitz was told this, he agreed his representatives could sign the deal, and that all units would surrender at 23:01 on 8th May 1945.

But this still wasn't the end. There was confusion over whether the Soviet delegate could sign the agreement, and then Moscow protested that Doenitz was still continuing to withdraw units westwards away from the Red Army. The surrender document was amended, and was signed not by Doenitz but by the heads of the three German armed forces. It still went into effect on 8th May 1945: VE Day, although by Moscow time it was the 9th. But it was of no importance when it was. The war in Europe was over. The ten days in which Nazi Germany fought the war without Adolf Hitler at the helm were at an end.

The second signing of the German Instrument of Surrender. Second time lucky...

On 23rd May, the game was up for the Flensburg government. Its members were arrested, and on 9th June the four Allies issued a declaration that as Germany had no government, they would assume control over the country for the time being. Planted in this was the seed of the Cold War, and of a divided Europe. The mistrust which came to blight the world in the later 20th century can be seen in the squabbles and arguments over the negotiations with the Flensburg government.

The arrest of the Flensburg government, 23rd May 1945

Another idea which the Flensburg government bequeathed the post-war world was just as sinister. The administration came into being as the true extent of the horror of horrors of the 20th century was being unveiled. The scenes at the camps of the Final Solution prompted revulsion around the world. Doenitz’s government, aiming to be given control of post-war Germany, needed an answer, fast. They blamed the SS, and elements within the Nazi party, for the violence and savagery. The armed forces, had not been to blame. Doenitz himself benefitted; despite being Hitler's chosen successor, he emerged with a good reputation, and thousands attended his funeral in 1980. By downplaying the guilt of the German leadership, and pinning the blame on some bad apples, the 'myth of the clean Wehrmacht,' and the very beginning of Holocaust denial, can just be seen.

One last final way that the Flensburg government impacts Germany today. The surrender document was signed by the German High Command. Technically, no government had agreed to Germany ending the war. The Allies claimed this was because Germany's government had disintegrated in the collapse of the Nazi regime; this is one of the reasons they were so keen to avoid acknowledging Doenitz as President, as it would make their assumption of total power over Germany more awkward if there was still a German government functioning. But it also gave rise to the idea that the German state had never surrendered, and still exists somewhere. In recent years, the German police have struggled with the Reichsburger movement. Their claim? That the German government never surrendered to the Allies, and they are claiming it for their own.