For the real question is whether the 'brighter future' is really always so distant. What if, on the contrary, it has been here for a long time already, and only our own blindness and weakness has prevented us from seeing it around us and within us, and kept us from developing it?

Vaclav Havel, The Power of the Powerless, 1978

Although it is often presented as such, the spectacular collapse of communist authority in East Germany, with the Berlin Wall and inner German border thrown wide open, was not the end of Soviet rule in Eastern Europe. The revolutions of 1989 came in waves, and were an unpredictable rollercoaster for those caught up in them.

The government of Czechoslovakia believed it could ride out the storm. A highly repressive society, even by Soviet-bloc standards, Czechoslovakia also had raw memories of the last time it had tried to ease the shackles of communist rule. The Prague Spring, a period of liberalisation in the mid-1960s, was met with a Warsaw Pact invasion in the summer of 1968. Ever since,

International Student's Day began in Czechoslovakia, marking a confrontation between Nazi occupiers and students at the Charles University on 17th November 1939. On 17th November 1989, students gathered in Prague to mark the event, and protest against the defiance of the Czechoslovak regime, which was stubbornly resisting change even as communist dictatorships collapsed around it. The Czechoslovak state responded in the only way it knew how. It sent in the riot police.

Czechoslovak riot police confront protesting students, 17th November 1989.

What exactly happened is still a matter of fierce debate. Rumours spread that a student was dead. Others later claimed he was an agent of the StB, the feared secret police, simply play-acting, to try and discredit the students. Others said he was simply overcome with emotion. What exactly happened is not important.

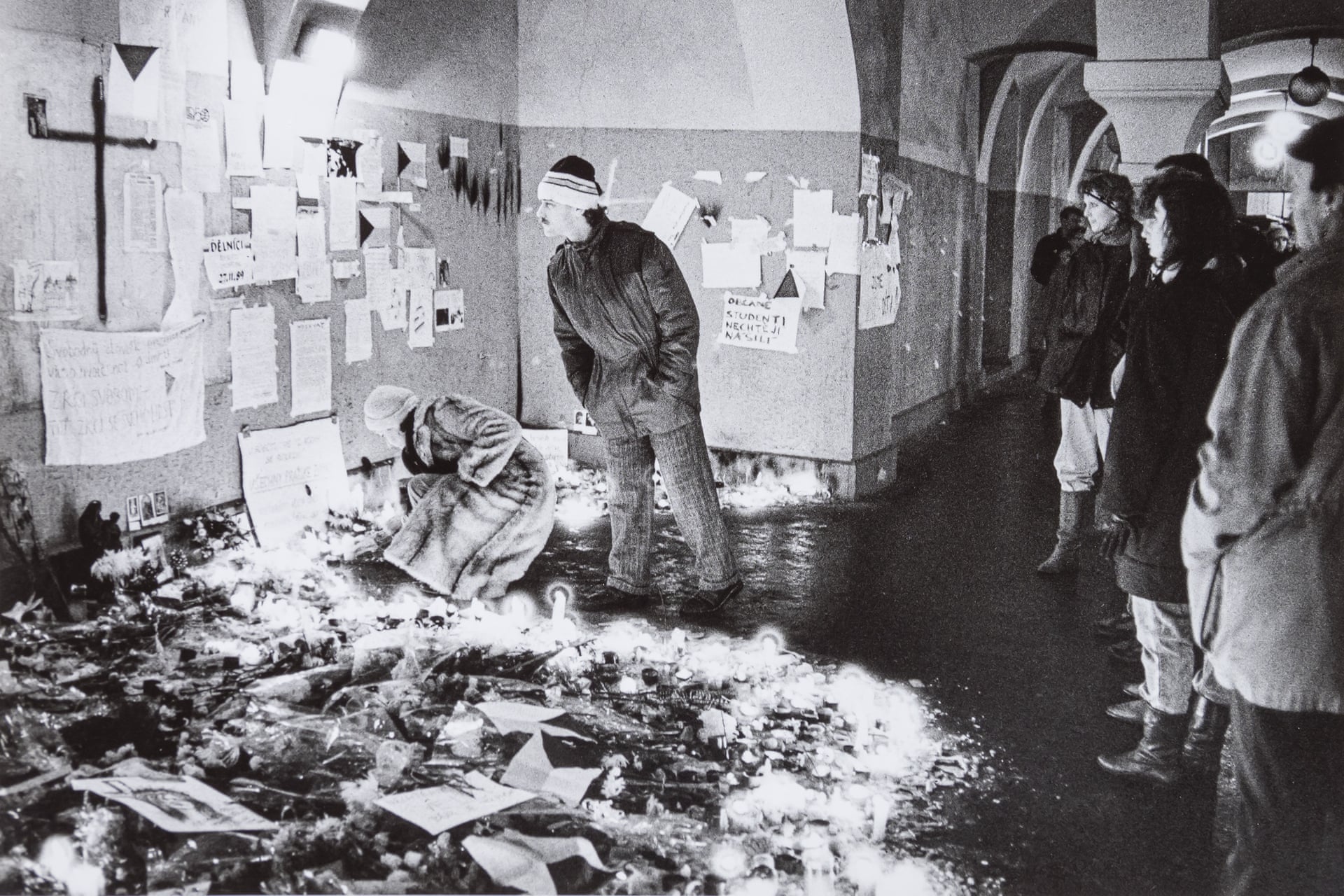

Memorial to the students, 23rd November 1989

What happened next is. Czechoslovakia had a long history of underground dissident thought. In the late 1970s, Charter 77 had been signed, committing dissidents to challenge the government on human rights grounds. In November 1989, it began to emerge from the shadows. The figurehead of the dissidents (although he hated that term) was Vaclav Havel, a playwright. He had spent most of the 70s and 80s in and out of jail for his plays and political essays. As rallies began to be held, and theatres and students went on strike, the cry went up: 'Send Havel to the Castle!' Prague Castle was the seat of the president. Two political bodies, Civic Forum and its Slovak sister Public Against Violence, sprung up out of nowhere to challenge the legitimacy of communist rule. The Churches threw their weight against the regime. And, most symbolically of all, the leader of the Prague Spring, Alexander Dubcek, left twenty years of internal exile and re-appeared on the scene, cheered enthusiastically wherever he went.

Protesters confronting Czechoslovak riot police, November 1989

Rally in Wenceslas Square, Prague, 24th November 1989

In the end, it was all too much. On November 24th, the entire communist leadership resigned. Within a month, the communists had been ousted from government, and the demonstrators had got what they wanted: Havel was installed as President of Czechoslovakia.

The once and future kings- Havel embracing Dubcek upon hearing that the communist leadership had resigned, 24th November 1989

The historian and journalist Timothy Garton Ash summed up the end of communist rule best:

In Poland it took 10 years; in East Germany 10 weeks; in Czechoslovakia 10 days.

Most of the pictures came from this Guardian article: https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2019/nov/16/czechoslovakias-velvet-revolution-1989-in-pictures