On December 14th, 1918, the country voted. As it did so, it changed, irreversibly. It was the first step on the final stage of change, from the autocratic, imperial power we had been, to the modern representative democracy we are today.

1918 was the first electoral contest in which the property qualification for men was removed, as per the terms of the Representation of the People Act of 1918. Now, all men could vote in the constituency in which they lived, provided they were over 21, or over 19 in the case of those in the armed forces. 5.6 million men were added to the electorate, the largest ever increase. No more would the money or status of the individual voter impact on the act of voting for the government.

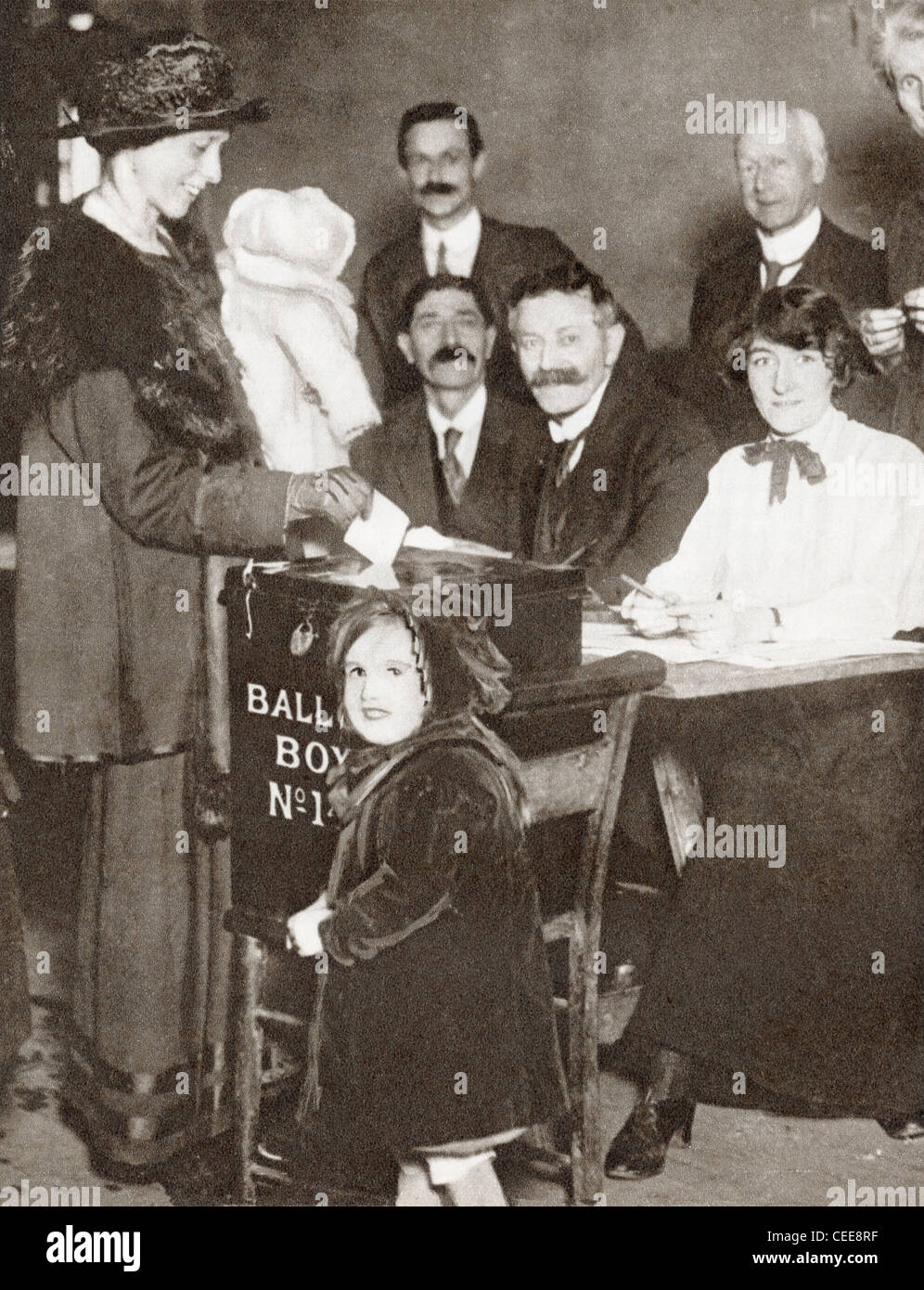

More famously, this was the election in which women could vote for the first time.

One of Britain's first female voters, casting her vote a century ago today

Well, not exactly. Before the 1832 Great Reform Act, there had been plenty of female electors. From the Middle Ages until 1832, the franchise was determined by your wealth; any rich enough woman would be enrolled. In practise, the only women with sufficient independent wealth were widows. These early participants in the first pangs of electoral democracy are frustratingly hard to spot in the historical record, but they are there, ghostly echoes of a forgotten world. In a by-election in Elizabethan Aylesbury, comments were made about women doing the voting. Complaints were made when women in Norfolk voted for the Long Parliament in the 1640s. These scraps are all we have of what was clearly a much bigger picture.

But the door was firmly slammed shut by the Great Reform Act; it explicitly restricted the franchise to 'male persons.' Even as that electorate widened to encompass more and more men, it remained sealed off to female voters. And yet, local election rolls from the 1840s onwards show that female voting was very much still alive at parish and municipal elections. The government did eventually pass some concessions. Single rate paying women were allowed to vote in local elections in 1869, and from 1894 this was expanded to cover married women. In 1867, an error by a polling clerk enabled elderly Lily Maxwell, a widowed shop owner, to vote in a parliamentary by-election in Manchester, capturing national attention and sparking many of the early suffrage societies.

What is true is that 1918 marks the first time a significant number of women voted in a British election. Yet the recent slaughter had taken its toll on the country. Were the franchise to have been expanded to encompass all women, they would have constituted the majority of the electorate. As a result, the 1918 Representation of the People Act specified that the only women who could vote were to be over 30and owned or rented property worth more than £5, or was married to someone who did, or was a graduate of a university with a constituency. 8.9 million women were added to the franchise; a remarkable start, but still not quite there.

On this day, at the first point of asking, a female candidate was actually elected to the House of Commons, the self-declared mother of parliaments, taking over 60% of the vote in her constituency. Yet the overwhelming victor in the seat of Dublin St Patrick's did not take her parliamentary seat.

Countess Markievicz, the first woman elected to Parliament, campaigning in a by-election in 1917

This wasn't due to a ignoble protest about women voters by men, or a last minute legal challenge, or a push by the suffrage campaigners to get full equal voting rights. Constance Markievicz didn't take her seat in Parliament because she was in Holloway prison, imprisoned for protesting against wartime conscription. Even had she been a free woman, she had not intention of going to Westminster. This is where the third reason this election is so important becomes clear. The 1918 election marks the beginning of the endgame of British rule over Ireland.

At Easter 1916, a ragtag band from the Irish Republican Brotherhood had staged an uprising across Ireland, in an attempt to use Britain's distraction by the First World War to drive them out of Ireland. The Easter Rising failed miserably, with the tiny numbers of rebels overwhelmed by the full military might of the most powerful empire on Earth, their leaders executed or thrown in prison. The self-proclaimed Irish Republic had lasted less than a week.

By 1918, resentment seethed across Ireland. Resentment at the treatment of the Easter rebels, resentment at London's attempts to impose conscription on the island, resentment at the imminent partition of Ireland along religious and political lines. When the election was called, the Irish Labour party agreed to stand down, to give a clear choice to the people of Ireland- vote for Sinn Fein and independence, or the Unionists to stay with Britain.

The results were wide open to interpretation. Of the 105 Irish seats, Sinn Fein took 73 out of the 105 seats. They took 46.9% of the votes across Ireland, but this amounted to 65% of the vote in the areas on the brink of leaving the UK; although in many areas they ran unopposed, and so no votes were cast in those areas. The Unionists took a quarter of the vote; however, this was mainly based on sweeping the seats in what was to become Northern Ireland- outside of this area, they only took one seat, in south Dublin, and the two seats given to the Irish universities. The old Irish Parliamentary Party, which for forty years had been the dominant voice of Ireland at Westminster, was crushed, holding a mere 6 of its 74 seats; however, it did take a fifth of the votes, and this represented more total votes than ever before, thanks to the expansion of the franchise. Quite what was to be made of this mess was anyone's guess.

Tensions were running high across Ireland

It fell to the MPs of Sinn Fein to make the next move. Those able to do so convened at the Mansion House in Dublin, saying they would boycott the Westminster Parliament, as it had no right to rule them. They called their new assembly the Dáil Éireann, and invited all Irish MPs to attend. The Unionists and moderate nationalists would not come. Only 27 of Sinn Fein's new politicians were free men. When the roll call was conducted, the many missing members were described as

é ghlas ag Gallaibh, or 'imprisoned by the foreigners.'

Their next move was just as bold. The Dail declared that, rather than having been crushed and buried in 1916, the self-declared independent Irish Republic was very much alive, now with a mandate from the people of Ireland. On the face of it, this was suicide. Every attempt by Ireland to sever the union unilaterally had failed, including one barely two years before. Only one part of the British Empire had ever succeeded in leaving British control by force of arms. And Ireland was nowhere near as powerful as the Thirteen Colonies of British America had been in 1776.

The words of the Dail could have ended up being an empty declaration, lost in the tides of history. But on the same day the Dail announced independence, remnants of the Irish Volunteers attacked a Royal Irish Constabulary wagon bringing explosives to a quarry in County Tipperary. In the shootout, two RIC officers were killed. The Irish Volunteers hadn't aimed to coordinate their actions with the Dail. But the Volunteers now saw themselves as the army of the Irish Republic, and with shots fired they set about attempting to achieve a military victory against Britain by force of arms.

The 1918 election did not yet see Britain become a perfect democracy. Although virtually all adult men could vote, the exclusion of 57% of women, and continued irregularities such as business voting and the university constituencies meant that it wasn't there yet. And the election in Ireland plunged one part of the United Kingdom into a vicious civil war, which had consequences lasting well into the 21st century.

And yet, this was the first election in British history which was something approaching democratic. In the previous elections of 1910, 7.6 million people had been able to vote. In 1918, the total possible number of voters was 21.4 million. And 1918 transformed the political landscape forever. David Lloyd George, the popular wartime leader, split the Liberal Party. His supporters continued in government with the Conservatives. The Liberals who didn't follow him into this unholy alliance were crushed at the polls. But Lloyd George's supporters were only saved by their pact with the Tories. Although they came fourth in terms of seats, the second placed party in terms of the vote share, with a fifth of the voters supporting them, was the Labour Party. As the Liberal star waned, the Labour star waxed. The modern political landscape, recognisable to us today, was being born.

I got a brother in that land

I got a brother in that land

I got a brother in that land

Where I'm bound

Where I'm bound

I got a sister in that land

I got a sister in that land

I got a sister in that land

Where I'm bound

Where I'm bound

Come and go with me to that land

Come and go with me to that land

Come and go with me to that land