Was the Leader of Her Majesty's Most Loyal Opposition there to throw his weight behind the campaign to save us from ourselves? He was not. Instead, Jeremy Corbyn was in Geneva, marking 20 years since the arrest of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in London, on charges of human rights abuses.

This year, I read the excellent Pinochet in Piccadilly, which examined the historic ties between Britain and Chile. From 19th century economic imperialism, to the student Jack Straw visiting the Allende government, the coup that had Allende killed, Pinochet's outriders of Thatcherism using Chile as their economic test lab, and finally Pinochet's fate being argued out in the House of Lords, the ties between Britain and Chile run deep, especially where Pinochet is concerned.

This book was written in the year 2000, two years after Pinochet's arrest in London. It was still fresh from the events. And yet Jeremy Corbyn doesn't make a single appearance. Many of the participants were interviewed, including the Chilean exiles who staged a vigil outside the House of Lords while Pinochet's fate was debated. Not a single sign of the MP for Islington North. That is not to say that Corbyn was not involved in the anti-Pinochet struggle. It was a popular left wing position after the coup, and until Pinochet was dragged from power. It is widely regarded as the issue that ignited Corbyn's passion for foreign affairs. But his position and role were so unremarkable that a book about the subject, written at the time, failed to mention him.

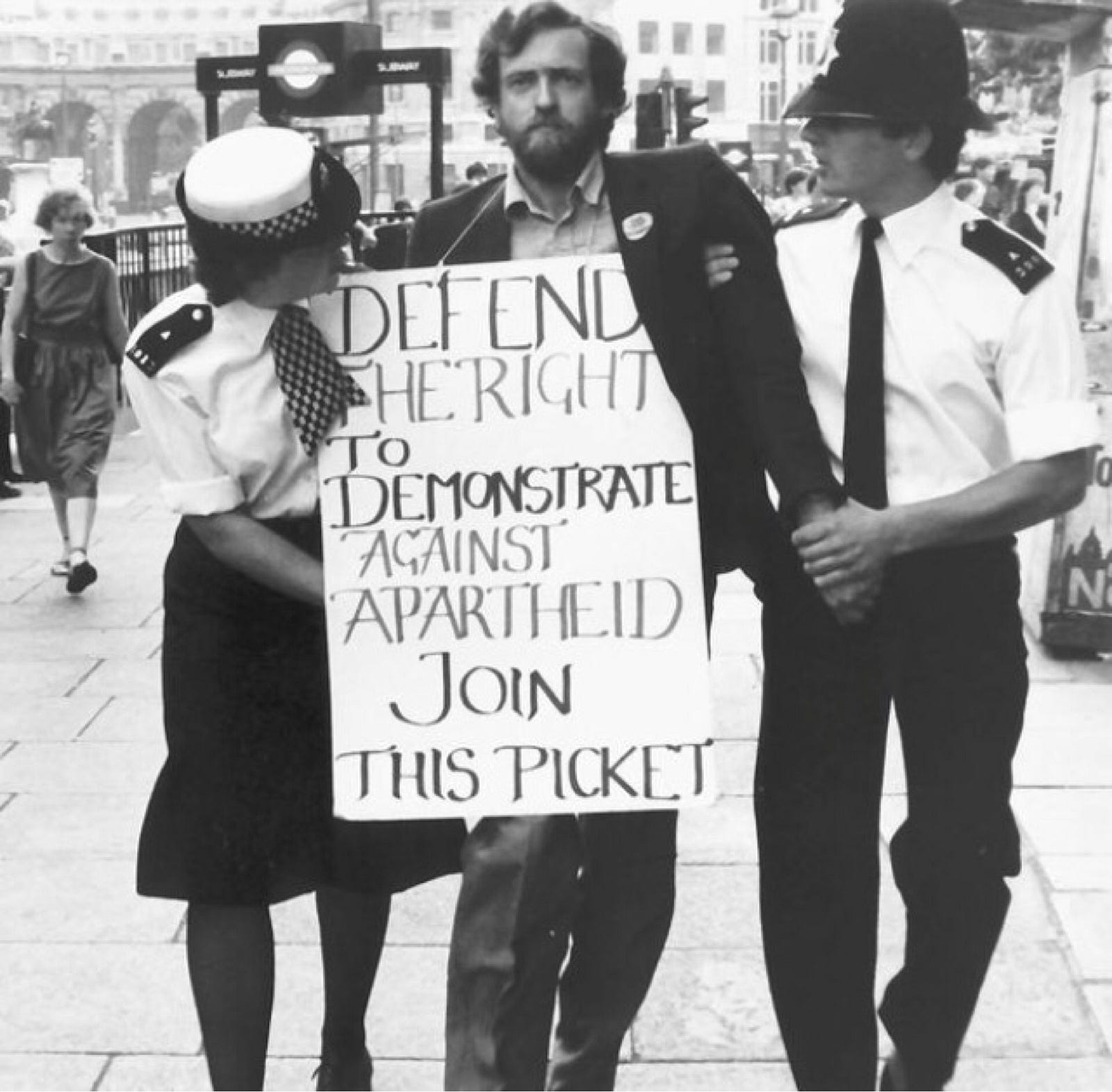

Corbyn campaigning against Pinochet

This Corbyn trend is not unique to Britain and Chile. Since being unexpectedly catapulted from utter obscurity to the leadership of the UK's largest leftist political force in 2015, there has been a big push on Corbyn's image. His years of engagement in various foreign affairs issues of the later 20th century have been held up as a virtue, which they undoubtedly are. However, as many of these events recede beyond memory for most people, there is a danger that the myth of Jeremy Corbyn will distort his part in these events.

Nowhere is this clearer than with regards to the Northern Irish Troubles. Corbyn and John McDonnell were long time supporters of a United Ireland and Sinn Fein, and by extension at that time the IRA. Whenever this is now raised, the response is to say that it was because they were exploring every possible avenue to bring about peace and stop the appalling sectarian carnage that engulfed Northern Ireland in the later 20th century.

Which again would be grand if anyone could point to a single moment where their actions had some influence. Corbyn voted against the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, the first (and as it turned out, faltering) step on the road to peace. Neither of them played any role in the Good Friday Agreement, or the torturous process afterwards by which the IRA was persuaded to disarm, nor the unionist parties persuaded to share power with those who had until recently been murderers. John McDonnell's claims he was trying to persuade the IRA to disarm in 2000 especially fly in the face of this timeline. Any history book on the Troubles doesn't contain their names at all.

Signing of the Good Friday Agreement, April 1998. Definitely no Corbyn or McDonnell there...

The same goes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The summer was dominated by stories about Corbyn's links to the various Palestinian groups fighting the Israeli government. And yes, Corbyn is a long term supporter of the Palestinian cause. In this, he was ahead of the curve, as Israel has traditionally had a lot of support from within the UK Labour party. Only with the savage war in Lebanon during the 1980s, and as occupation began to take its toll, did this start to shift within the Western left. But his claims to have been at the PLO cemetery in Tunisia to promote peace are laughable. When the final analysis of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is written, his contribution won't even merit a footnote within a footnote.

Signing of the Oslo Accords, 1993. I doubt there's a single Briton there, let alone backbench Labour MPs...

Surely Corbyn's one area of foreign policy success must be South Africa. After all, there is this photo, which did the rounds last year:

I'm not going to repeat much of the analysis of this, which can be seen here. But Corbyn was not a lone voice in the 1980s in opposing apartheid. Since Harold Macmillan had told the apartheid parliament in 1960 that the 'winds of change' were blowing through Africa, opposition to the racial state had been formal British policy, backed up by widespread global support. The African National Congress, the party of Nelson Mandela, was based in London from 1978 until 1994; the South African government had to resort to sending spies to plant bombs in the offices to try and get at them, as they had no help from the British government in moving against what was labelled a terrorist organisation. The rally that this picture was taken at was organised by a Trotskyite fringe group, and was not supported by the main British anti-apartheid groups. Two other Labour MPs were arrested. Aligned with the right side of history? Corbyn certainly was. A lone voice standing up bravely against apartheid? Not really.

Perhaps where Corbyn can legitimately claim to have been a trailblazer is the war in Iraq. As the world watched with baited breath, tens of millions around the globe used 15th February 2003 to march against the war. Corbyn did give a speech at the million strong march in London, under the banner of the Stop the War Coalition. You can see it here.

The poor quality of the few pictures of Corbyn at the rally probably tells you more than any words I can spill on the subject

If you look at the BBC news report from the day, they list a huge litany of speakers. Charles Kennedy, as the leader of the Liberal Democrats, the largest UK-wide political party to come out against the war. Jesse Jackson, Tariq Ali, Mo Mowlam, Ken Livingstone, Vanessa Redgrave, Bianca Jagger, Tony Benn, Harold Pinter- all are noted for their contribution. Corbyn is not.

This is the politician that did most to articulate the anti-war case in 2003.

Blair refused to bow to public pressure. But he still had to face the House of Commons, in a moment of high political drama. Labour was deeply divided on the issue. Junior ministers resigned, and Robin Cook delivered one of the finest speeches in modern Parliamentary history in resigning from the Cabinet to vote against the war. No one could be quite sure how events would play out.

Cook's resignation speech- Look who picked a good spot behind him!

When MPs voted, Blair had his majority. 412 MPs voted to support the war in Iraq, as against 149 against, and 94 abstentions. But this belied the Labour splits. Only 254 Labour MPs had voted with their own Prime Minister; 84 of them voted no outright, and a further 69 abstained. Blair had been saved by the Conservatives, UUP and DUP. Yes, Corbyn had done the right thing. But he was not a leading light, nor was he alone in voting against the war. In that, he was joined by 83 other Labour MPs, 52 Liberal Democrats, 9 Scottish and Welsh nationalists, two Conservatives, 1 SDLP and 1 independent MP.

While on many of these issues, Corbyn was indeed on the right side of history, he was not alone, nor a driver of events. Most importantly, when the history books are written, he will at best be a footnote in these events. The role his supporters wish to ascribe him, as the John the Baptist of foreign affairs, the long voice crying out in the wilderness, heralding better things to come, is simply not true.