Sandbank sits on Holy Loch, which links directly to the sea. Since 1961, their little village was the closest to a new US Navy base, the European site for their submarine fleet. On that October morning in 1962, all the submarines were missing. They had slipped away in the night, and were at that moment out in the North Atlantic. From deep beneath the waves, their commanders were selecting towns and cities deep inside the Soviet Union. Each would be the target of a Polaris missile, far more powerful than the atomic bombs which had obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki seventeen years previously. In those boats, enough destruction existed to kill tens of millions. And they were being prepared for launch.

In London, the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, was making an unprecedented decision. He had summoned his Cabinet to a Sunday meeting, the first since the Second World War. On the agenda was one item. The government would begin to move civil servants and military personnel out of London, into the network of bunkers and tunnels underneath the Cotswold Hills, known as TURNSTILE. This was the first stage of Britain's plans to ensure some government survived the nuclear war that all believed was now virtually inevitable.

Macmillan could also update the Cabinet on his discussions with the American President. He had been speaking daily to John F Kennedy. For it was Kennedy who had, in part, brought the world to the brink of Armageddon. Five days previously, he had revealed to the world that American spy planes had found Soviet nuclear missiles on the island of Cuba, a mere 90 miles from the Flordia coast. Kennedy had already been stung by Cuba; in April 1961, US-sponsored Cubans had tried to invade Cuba to overthrow the new communist government of Fidel Castro. It had been a disaster, and Kennedy had been made to look ridiculous. However, Castro had been spooked by the US-sponsored invasion, and had asked the USSR for help. The USSR could not ignore the only communist country in America's backyard, and so their leader, Nikita Khrushchev, approved the placing of nuclear missiles in Cuba. Now they had been found.

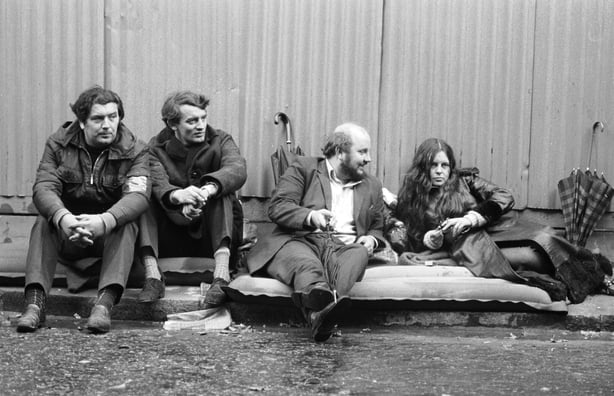

The photo which almost triggered a world war

Kennedy had faced down advisors in his administration and military who wanted to invade Cuba, or bomb the missile launch sites. Instead, he had opted for a blockade, or 'quarantine' of Cuba, to prevent more missiles arriving, and demanded the exisiting missiles were removed. He was clear that any use of the missiles would be considered a direct attack by the Soviet Union on America, and would lead to war between them. He hoped this strong language and a step short of force would be enough.

Kennedy's speech announcing the discovery of Soviet missiles on Cuba, 22nd October 1962

By Saturday 27th October, it looked as if it had failed. The Soviet missiles were still in Cuba, and were still being prepared for launch. An American U2 spy plane was shot down that morning over Cuba, the pilot killed. Kennedy was running out of options. Castro was asking the USSR to approve the missiles for pre-emptive use against the USA. It seemed as if only an invasion would stop him, but that would mean a third world war. The US communicated to their NATO allies that they needed to be ready to withstand an attack by the Warsaw Pact.

Meanwhile, out at the blockade, US Navy ships were dropping dummy explosives on a Soviet submarine, not realising it had nuclear weapons on board, and that the captain believed the explosives targeting him were real. Another U2 spy plane over Alaska had got lost, and had crossed into Soviet airspace, where it was intercepted by Soviet jet fighters. Not for nothing was this day later called 'Black Saturday' by those working in the White House. The world was teetering on the edge of a nuclear war.

The Soviet submarine B59, eventually forced to the surface by American explosives

It should come as no surprise that the world did not end that Saturday in 1962. Overnight, US diplomats had been busy translating a long letter they had receieved from Khrushchev. In it, he had offered to remove the missiles if America promised never to invade Cuba again. Khrushchev then made a public broadcast, adding the catch that the USA would have to remove their own nuclear missiles from the Turkish border with the USSR. Kennedy replied to Khrushchev's first letter, but ignored the second message in public. It seemed like a long shot.

In Moscow, Khrushchev knew that the situation had spiralled out of control. He had given explicit instructions for force to not be used against American forces, yet that was clearly being disregarded. It would be very easy for the situation to blunder into an exchange of nuclear weapons in which millions would perish. So when Kennedy's offer came in, Khrushchev took it, without consulting the rest of the Soviet government. It was made easier when the Americans assured the Soviets in private that the American missiles in Turkey would be dismantled as well.

And so by the skin of our teeth, the world made it through

To the world, it looked as if the USA had outsmarted the USSR. The secrecy of the Turkish missile deal lasted into the 1990s. Kennedy repaired his reputation, which had been badly damaged by his earlier blunders over Cuba. Khrushcehv meanwhile was living on borrowed time. He was deposed in 1964, in part because other Soviet politicans were furious that it looked as if the USSR had backed down. Of course, by that point Kennedy had passed into myth and legend, the victim of an assassin's bullet.

The Cuban Missile Crisis remains the closest the world deliberately came to a nuclear war. Black Saturday, 60 years ago today, was the day the world came closest to ending deliberately. And it was only by a stroke of good fortune that the human race lived to see Sunday 28th October, and all those days since.