How things don't change. Forty years ago today, things look very similar to how they do today. Today marks forty years since the last time a UK government was brought down on the floor of the House of Commons in a no confidence motion.

James Callaghan had become Prime Minister in 1976. That was pretty much his last piece of good luck. His majority gone the day he took office, amidst a horrendous economic storm, and the creditors of the IMF circling, it had been a miracle that Callaghan had survived the year without his government falling. In fact, by late 1978, Labour had pulled even with the Conservatives in the opinion polls. Callaghan mulled an early election. In the end, in September 1978, Callaghan went on TV and dropped the bombshell. He would not go to the polls, but would wait until next year.

Callaghan showing the balancing skills that kept him in office against the odds for three long years

Big mistake. At the very same moment, the Ford car workers in Dagenham went on strike for higher pay. The government wanted to restrict pay rises to 5%. The Ford workers got 17%. This triggered a series of walkouts across huge swathes of industry. It was nicknamed the Winter of Discontent.

Britain in the Seventies was no stranger to strikes. The 1971-72 strike by the miners had caused blackouts, and the Three Day Week of 1974 was unprecedented in Britain's postwar history. The Winter of Discontent was far less disruptive than either of those events. But it marked the moment when the Labour government of 1974-79 went into terminal decline.

The Winter of Discontent

If it was the Ford workers in Dagenham that began the collapse of James Callaghan's government, it was voters in Scotland and Wales who delivered the crippling blow. At the depths of unpopularity, in early March 1979, the government was committed to hold devolution referendums about establishing assemblies in Scotland and Wales. The Welsh assembly was roundly rejected; the Scottish Assembly was a more complicated case, as voters did pass it, but not by the required margin. The SNP and Plaid Cymru now had no reason to prop up Callaghan's government, and the SNP made it clear they would vote to bring the government down. The Conservatives, seeing their chance, laid down a motion of no confidence.

But Labour were not going down without a fight. Talks were held with Plaid Cymru, the Welsh nationalists, and the breakaway Scottish Labour Party, who both agreed to support the government. A freedom of information law was offered to Clement Freud to try and peel him off from the rest of the Liberals. Some Ulster Unionists were brought onside by promising them a pipeline to Northern Ireland. This agreement nearly fell apart when the deal was signed in green ink by accident; it had to be quite literally taped back together.

More worrying was the health of Alfred Broughton, a West Yorkshire Labour MP. Broughton was terminally ill, and his doctors warned that to move him from Batley and Morley down to London would kill him. The Labour whip Walter Harrison asked his Tory counterpart, Bernard Weatherill, if they could reach an agreement for an abstention. Weatherill refused, then offered to abstain himself. Harrison said no, thereby saving Weatherill's career, and quite possibly allowing him to become the Commons' Speaker four years later as a result.

The night itself was one of high tension. There are stories of Labour whips prising half-drunk members out of the pubs and bars of Westminster, where they'd been detained by journalists hostile to the government. Searches were conducted of the Palace of Westminster to make sure there were no lost MPs, or to spot opposition MPs being hidden to vote at the last possible second, to confuse the numbers. It was bordering on chaos.

In the chamber of the House of Commons, the atmosphere was electric. Callaghan, knowing the hour of reckoning had come at last, gave a good defence of his government, branding the SNP as Turkey's voting for an early Christmas. Thatcher's speech fell flat, living up to her then nickname of Cautious Margaret. Gerry Fitt, the SDLP member for West Belfast, decried the government's hardline militaristic attitude to Northern Ireland, and said he couldn't go into the lobbies with his socialist allies tonight. Frank Maguire, the elusive Republican MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, turned up to 'abstain in person.'

But the real star of the night was Michael Foot. The leftwing firebrand, who had become Callaghan's Leader of the House of Commons, put in the performance of his life. He savaged the uncomfortable bedfellows arranged opposite Labour, pouring scorn on their opponents; he famously described David Steel, the Liberal leader, as having "passed from rising hope to elder statesman without any intervening period whatsoever." In his final paragraphs, Foot launched an impassioned defence of Labour's achievements in office across the 20th century. Were he never to have presided over Labour's sorry performance in 1983, he would have been far more fondly remembered for this.

Yet despite all of Foot's rhetorical brilliance, the desperate rushing about of the whips, the timidity of Mrs Thatcher, the result went down to the wire. In a pre-TV era for Parliament, people were forced to rely on radio to discover what was going on. As the tellers lined up to deliver the result, the Tory tellers stood on the losing side. Roy Hattersley, Labour's Prices and Consumer Protection Secretary, watched Thatcher go white, and mouth "I don't believe it."

It wasn't to be believed. In the crush, the tellers had stood in the wrong place. The government had 310 votes, to the opposition's 311. The House of Commons had no confidence in Her Majesty's Government. As the opposition benches erupted in cheers, and the Labour benches were led by backbencher Neil Ninnock in singing 'The Red Flag,' Callaghan got to his feet for the last time as Prime Minster. "Now that the House of Commons has declared itself, we shall take our case country."

More worrying was the health of Alfred Broughton, a West Yorkshire Labour MP. Broughton was terminally ill, and his doctors warned that to move him from Batley and Morley down to London would kill him. The Labour whip Walter Harrison asked his Tory counterpart, Bernard Weatherill, if they could reach an agreement for an abstention. Weatherill refused, then offered to abstain himself. Harrison said no, thereby saving Weatherill's career, and quite possibly allowing him to become the Commons' Speaker four years later as a result.

The night itself was one of high tension. There are stories of Labour whips prising half-drunk members out of the pubs and bars of Westminster, where they'd been detained by journalists hostile to the government. Searches were conducted of the Palace of Westminster to make sure there were no lost MPs, or to spot opposition MPs being hidden to vote at the last possible second, to confuse the numbers. It was bordering on chaos.

In the chamber of the House of Commons, the atmosphere was electric. Callaghan, knowing the hour of reckoning had come at last, gave a good defence of his government, branding the SNP as Turkey's voting for an early Christmas. Thatcher's speech fell flat, living up to her then nickname of Cautious Margaret. Gerry Fitt, the SDLP member for West Belfast, decried the government's hardline militaristic attitude to Northern Ireland, and said he couldn't go into the lobbies with his socialist allies tonight. Frank Maguire, the elusive Republican MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, turned up to 'abstain in person.'

But the real star of the night was Michael Foot. The leftwing firebrand, who had become Callaghan's Leader of the House of Commons, put in the performance of his life. He savaged the uncomfortable bedfellows arranged opposite Labour, pouring scorn on their opponents; he famously described David Steel, the Liberal leader, as having "passed from rising hope to elder statesman without any intervening period whatsoever." In his final paragraphs, Foot launched an impassioned defence of Labour's achievements in office across the 20th century. Were he never to have presided over Labour's sorry performance in 1983, he would have been far more fondly remembered for this.

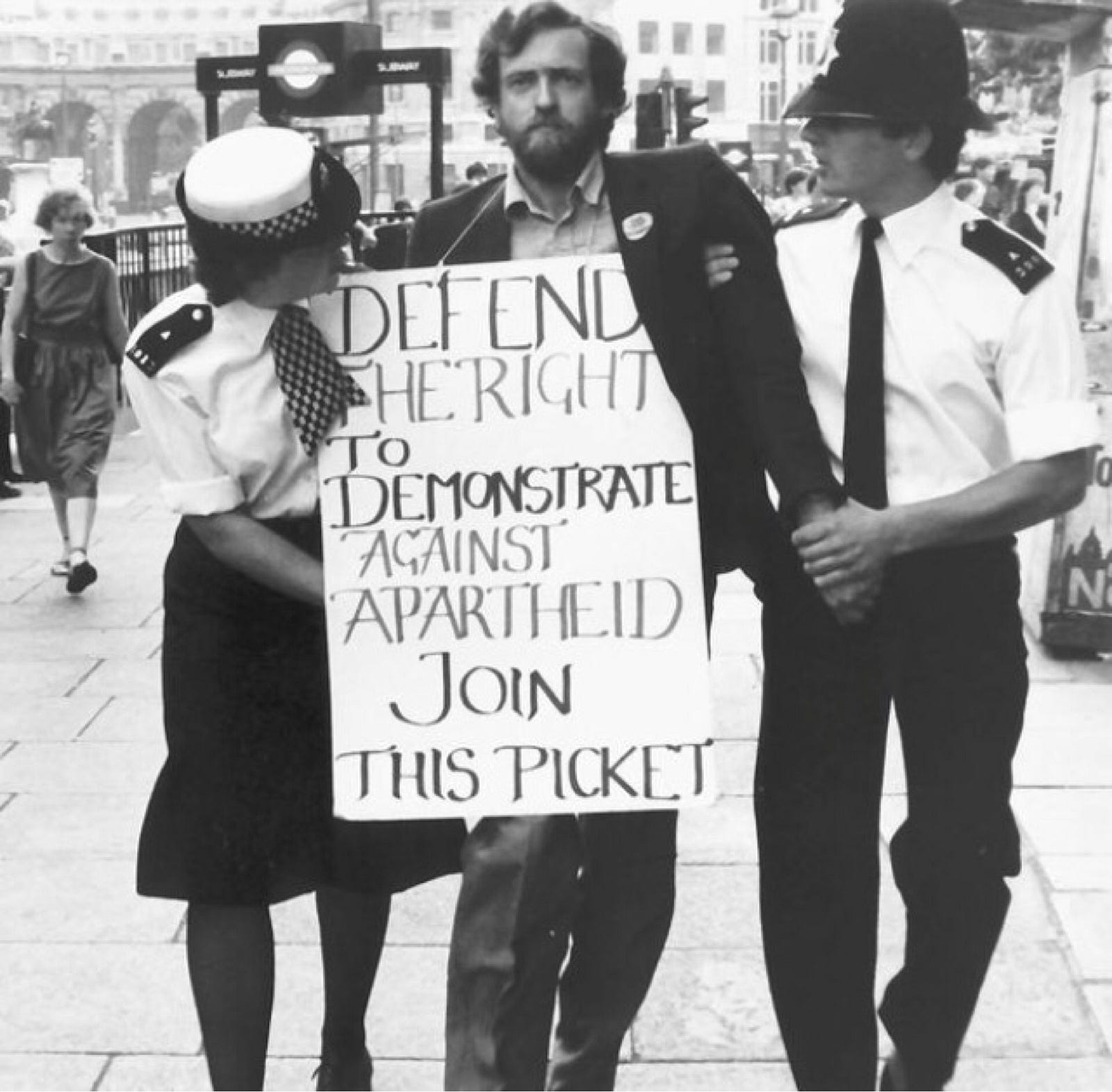

The hero of the hour

Yet despite all of Foot's rhetorical brilliance, the desperate rushing about of the whips, the timidity of Mrs Thatcher, the result went down to the wire. In a pre-TV era for Parliament, people were forced to rely on radio to discover what was going on. As the tellers lined up to deliver the result, the Tory tellers stood on the losing side. Roy Hattersley, Labour's Prices and Consumer Protection Secretary, watched Thatcher go white, and mouth "I don't believe it."

It wasn't to be believed. In the crush, the tellers had stood in the wrong place. The government had 310 votes, to the opposition's 311. The House of Commons had no confidence in Her Majesty's Government. As the opposition benches erupted in cheers, and the Labour benches were led by backbencher Neil Ninnock in singing 'The Red Flag,' Callaghan got to his feet for the last time as Prime Minster. "Now that the House of Commons has declared itself, we shall take our case country."

The aftermath of this dramatic night cannot be understated. The election called for May 1979 saw the Conservatives sweep into power. They would remain in office for another 18 years, and transform Britain completely in that time, as monetarist economics and shock therapy would decimate industry and huge swathes of the country. Especially grimly ironic was the fact that these changes hit Scotland the hardest; a cry still levelled against the SNP is that in its opportunism it let in Thatcherism. But the 1980s were not kind on anyone on the left. Labour would come close to destroying itself in the years that followed, in a civil war which makes their current problems look like a picnic in comparison. Many confidently predicted that there would never be another Labour government, and that James Callaghan's last stand on the floor of the House of Commons was the dying gasp of a political movement.

And yet, this was not quite the full picture. Labour may have been defeated in 1979, but it actually added 70,000 votes to its October 1974 share. An increased turnout, and huge shifts from the Liberals and minor parties, put Mrs Thatcher into office, not any collapse of the Labour vote. The Winter of Discontent did not taint Labour, as many claimed. Clearly, Callaghan was doing something right. But this cannot hide the fact that 1979 represented a catastrophic reversal for Labour. The next Labour Prime Minister to rise to the despatch box had only been a member of the party for four years in 1979, and hadn't even started looking for a seat in Parliament. An entire generation would come of age before the Tories were removed from power.

The last old Labour government had gone down fighting in a blaze of glory, having been kept alive on borrowed time and through sheer force of will. But that can't hide how much of a disaster it was, the night the government fell.

If you want to relive the entire night in all its glory, look no further!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifMiJ7DcUi0 BBC documentary from 2009

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZqzIZVJOQdk BBC coverage from 1979

If you want to relive the entire night in all its glory, look no further!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifMiJ7DcUi0 BBC documentary from 2009

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZqzIZVJOQdk BBC coverage from 1979