In August 1969, the Republican Labour MP for West Belfast, Gerry Fitt, found himself taking shelter with some of his constituents in a shop along the Falls Road in Belfast. Outside, there was chaos. Northern Ireland was teetering on the brink of a total collapse in law and order. Clashes between Unionists and Nationalists were blighting every major town and city. The Royal Ulster Constabulary was widely perceived to be taking the side of the unionists; rather than suppressing the disorder, they were fuelling it. People were being forced from their homes, in scenes more akin to a pogrom than a riot in post-war Britain.

Fitt's constituents begged him to use his influence with the Home Secretary, Labour's James Callaghan, to do what had been done in Derry several days previously, and send in the British army to keep the two sides apart. So Fitt used the phone in the shop to talk to Callaghan, and told him what the people wanted. "Gerry,' Callaghan replied, "I can get the army in, but it will be a devil of a job to get it out."

It is one of those historical occurrences that is a bit too neat, written with the benefit of hindsight. But it accurately reflects the contradictions and consequences of the events in the summer of 1969, when Britain sent troops to Northern Ireland.

The partition of Ireland in the 1920s had left deep scars. Northern Ireland was a predominantly Protestant and unionist polity, and the Ulster Unionist Party reigned supreme. "A Protestant Parliament for a Protestant people" ran the saying about the local government at Stormont, and it was accurate. Despite accounting for nearly a third of the population, the Catholic and nationalist population suffered from being treated as second-class citizens; it was harder for them to vote, and they took second priority in terms of jobs and housing. The security apparatus of the new state, the unionist dominated RUC and the B-Specials reservists, took a hardline on policing. Understandably, for they had seen their predecessors in British Ireland taken apart by the IRA, whose spectre haunted the newly partitioned state. This state of affairs persisted from the 1920s until the mid-1960s, with little attention from Britain, let alone the rest of the world. With its own Parliament and Prime Minister, Northern Ireland had a huge level of autonomy, and British politicians saw no need to upset the status quo. But with the birth rate in the nationalist community outpacing the unionist birth rate, this was a house built on sand.

It was events on the other side of the world that began to make the sands shift. In the Deep South of the USA, the struggles of the civil rights movement, standing against the segregationist Jim Crow laws, were beamed around the world, and held up as a symbol of the 1960s. This infectious air of progress through peaceful means caught on in Northern Ireland. In 1967, the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association, formed of a coalition of left wing groups, began to campaign for fairer voting, reform of the police, and an end to discrimination in jobs and housing. From 1968, they began to stage a series of marches across Northern Ireland.

The reaction of many unionists was little short of hysteria. They warned that to concede on these measures would start Northern Ireland on a path that would end with Irish unification, which would see the end of their way of life. They also claimed that the NICRA had been infiltrated by the IRA. This was true, but only as the IRA had pretty much abandoned the armed campaign and had committed its members to this venture to try and achieve Irish unity. The figurehead who emerged as the leading voice (ironically, as he was so loud) of the hardliners was Ian Paisley, the firebrand Protestant minister. Doubly ironically, it was Paisley's rhetoric that breathed new life into the loyalist paramilitary organisations, who prepared to defend their way of life by force.

In late 1968, a civil rights march went ahead despite being banned by the Northern Irish government. The RUC set on the march, and many were badly injured. The footage that emerged from the march looked very similar to the actions of the police in the American Deep South. In response, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O'Neill, introduced a mild package of reforms to meet the demands of the NICRA. But so febrile was the atmosphere that loyalist unionists cried treachery. An election called by O'Neill saw the Ulster Unionist Party split badly on the issue, and he was forced to resign. At the same time, a by-election to Westminster was won by Bernadette Devlin, only 21 years old, standing on the Unity ticket, which supported the NICRA. The outside world was beginning to notice that something was rotten in the state of Northern Ireland.

Which brings us to the summer of 1969. In Derry, a city so divided that even the name is politically contentious, a march to commemorate a Protestant victory in a battle in Irish history was held on August 12th. The march happens every year, but in this atmosphere it was a spark that ignited a tinderbox. Police clashed with citizens around the edge of the heavily Catholic Bogside area. Barricades were erected, and the police, joined by unionist civilians, got into running battles with nationalists. Tear gas was met with petrol bombs. In areas which were more mixed, families from the minority were forced out of their homes, which were destroyed. The RUC, badly out of its depth, called up the hated B Specials, which sent more fear through the Catholic community. The unrest began to flare up in Belfast, and other areas.

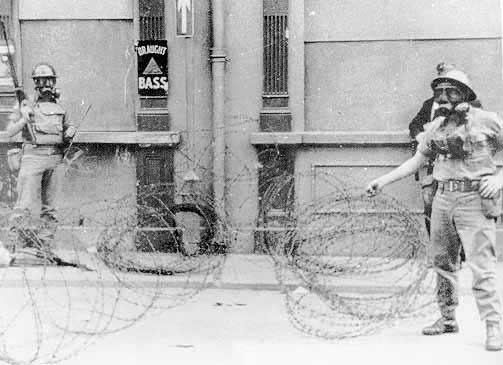

All of this was taking place in full view of the world's media, on the streets of a major Western democracy. The pressure to act was immense. Harold Wilson, Britain's Prime Minister, discussed with James Callaghan their options. If the government of Northern Ireland asked for help, it would be given, providing there were more reforms to meet the demands of the protesters. James Chichester-Clark, the new Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, bowed to the inevitable, and requested help from the British government. The army was sent to Derry on August 14th, and arrived in Belfast a few days later.

In light of later developments, the reactions seem bizarre. Many unionists detested the interference by the British government in their own affairs, especially when it was forcing them to make concessions. Dublin was furious at the move, but totally powerless to do more than complain. As for the protesters themselves, they were delighted with a more impartial face of law and order. "We've won, we've won, we've brought down the government" went the chant from the barricades. There are many stories of British soldiers being brought tea and cakes. After all, the soldiers had actually come to protect them, unlike their supposed saviours. 'I Ran Away' was graffitied all over Catholic areas, and contempt for the paralysis in the moribund IRA was widespread. The soldiers patrolled openly, with berets and safety catches on. The commander of the soldiers was delighted with the deployment, as he had heard that Northern Ireland's golf scene was second to none.

There were voices in the summer of 1969 that predicted the recent spate of violence would not be stopped by the arrival of British soldiers, and in fact would get worse. Callaghan and Wilson were under no illusions as to what they had done. The army knew that without a real political drive towards conciliation, the soldiers would soon be caught in the middle of an ugly conflict. And the events of 1969 did lead to a hardening of attitudes on both sides. On the unionist side, there was outrage that even the British government was forcing them to make concessions to the nationalists. For the nationalists, the reforms that accompanied the soldiers were nowhere near enough, and the soldiers soon came to be seen as part of the unionist state. The deployment of British troops caused a crisis in the IRA. It split, with those who wanted it to actually do something leaving and creating a new organisation dedicated to taking the fight to the British, the Provisional IRA. The seeds of the sectarian chaos of the early 1970s was being sown.

James Callaghan probably did not speak to an embattled Gerry Fitt over the phone in August 1969. But the anecdote perfectly encapsulates the possibilities and problems which existed in the deployment of British soldiers to Northern Ireland.

Soldiers from the Prince of Wales Regiment deployed on the streets of Derry, 14th August 1969

https://canvas-story.bbcrewind.co.uk/sites/usatc/ This site is an excellent summary, with pictures and archive video, of the story I have tried to tell.

No comments:

Post a Comment