On the evening of April 18th, 1521, a hall in Germany found itself packed

with people. Many of them were rich and powerful, and probably had better

places to be. But none of them wanted to miss the show about to unfold in front

of them. They were about to witness the real end of the European Middle Ages.

The Holy Roman Empire is one of the most misleading names for a country. For

starters, it covered modern-day central Europe, centred on Germany, but also

including Switzerland, northern Italy, Austria, and the Czech lands. By the

early 16th century, it was sometimes also called the German Nation.

It also wasn't much of an empire. Instead, the individual princes, cities,

and bishops of the Empire enjoyed enormous autonomy. Seven of them chose the

new Emperor- three bishops, and four secular princes. In that respect, at least

the name Holy was appropriate.

And so it was to the city of Worms that the Imperial Diet, or parliament,

was summoned in the spring of 1521. This was the first called by the new

Emperor, Charles V. Barely 21, Charles was also the king of Spain, Duke of the

Netherlands, and ruler of the vast Spanish possessions in the New World. This

powerful Renaissance prince had called the Diet partly to try and streamline

the way that the Empire worked. But the princes were waiting for something far

more consequential than administrative reform.

Against this collected might of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation

was brought a single man. All the princes and bishops, plus the Emperor

himself, were facing a lone monk, clad in the black robes of the

Augustinian order. They had seen him before. Yesterday, he had been brought

before the Diet, and shown a pile of books. He was asked if he recognised them.

He did indeed, he had replied. No surprise really; he was the author of all of

them.

The second question had proved a lot harder for the monk to answer. He had

been asked if he took back their contents. This seemingly easy question,

requiring a yes or no answer, had instead been met with a question of his own-

could he have time to think? The Diet had given him a day. Now, in the fading

light, they required their answer.

This university professor was no obscure cleric. He was the bestselling author

in all Germany, in the top three across all of Europe. His name was Martin

Luther. Luther had entered the history books three and a half years earlier,

when he had started an academic debate. Or rather, he had tried to. Appalled at

the brazen sale of indulgences in his native Saxony, conning the faithful into

parting with cash to rebuild St Peter's basilica in Rome, Luther had posted 95

ideas, or theses, written in Latin, onto the door of the church in Wittenberg.

This was the standard way of starting an academic debate at the time.

He had done far more than start an academic debate. His complaints against

indulgences, and the money flowing to Rome, had tapped a deep seam of

resentment in Germany. Not with Christianity, but with the relationship with

the Church in Rome. His ideas, translated into German, spread like wildfire

through Germany, helped by the fact that he had an easy to read, punchy writing

style.

For the Church, this could not go unanswered. But this was not yet the

defining clash of the early modern period. It was an academic dispute, between

priests, conducted in Latin. At first, meetings were held between Luther and

various other priests, to debate their ideas. But these meetings became more

and more heated. It was clear that what had begun as a debate over the technicalities

of salvation was rapidly escalating.

Things did not all go Luther's way. In 1519, he had been badly beaten in a

debate at Leipzig against Johann Eck, another theologian who was defending the

Catholic line. Eck had, from his point of view, forced Luther into a corner,

making him agree with many ideas of prominent medieval heretics. But this ended

up being a major own goal. Luther saw for the first time how much his ideas

were taking him away from the Catholic beliefs which had been universal in

Western Europe for centuries.

The war of words dragged on, with Luther writing increasingly bitter

criticisms of the Roman Catholic hierarchy and doctrines, and the Church

pushing back. Eventually, Luther was subjected to the worst act of social

exclusion that medieval Europe could muster. He was excommunicated by the Pope;

that is, thrown out of the Church, put beyond the community, and condemned to

suffer for all eternity in the next life. Undaunted, Luther burnt the Papal

bull of excommunication in the main square at Wittenberg. What had begun as an

attempt to talk around a minor theological issue was now spiralling out of

control.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Pope was incensed. Something had to be done to

put this turbulent priest in his place. So it was that Luther came to Worms in

April 1521. He had been promised safe conduct by Charles V, who had told the

Pope that he would deal with Luther; he was certainly not sending him to Rome.

On his way, crowds had greeted him like a modern celebrity. In his first

appearance before the Diet, Luther had equivocated when asked to retract his

beliefs. Now, a day later, his time was up.

Luther began by saying that yes, he knew his language had sometimes been

extreme, and for that he was sorry. But the ideas contained in them, he was

less willing to take them back. Only if they could be shown to be contrary to

Scripture or to reason would he retract, otherwise this was bound up in his

conscience. Popes and councils had both been shown to be mistaken in the past.

Conscience, he told the Diet, was above the authority of Popes, councils, and

the Church; indeed, it was a direct line to God. According to tradition, he

finished his refusal to back down by telling the Emperor, and the assembled

princes and delegates "Here I stand, for I can do no other. So may God

help me, Amen."

The Diet erupted. Eck, present once again, told Luther he was acting like a

heretic. Voices began to cry out "Into the fire," the traditional

form of execution for those whose beliefs did not conform to the Church's.

There was a precedent. A century before, the Czech priest Jan Hus, who had

shared many of Luther's beliefs (his had been a name Eck had invoked in his

trouncing of Luther in the Leipzig Debate) had been summoned to appear before

the Council of Constance, a great reforming Church council, to explain his

ideas. The cardinals and bishops had been so appalled by what they heard that

they ignored their promise to Hus of safe passage home, and had him burnt at

the stake.

Amidst all the chaos, only one person's view mattered. Charles V was

weighing his choices. On the one hand, he saw himself as the premier Christian

prince on Earth, the secular wing of a partnership with the Pope. Luther's

ideas were clearly heterodox, and could not be allowed to stand. On the other,

Charles was a man of his word, and he didn't want to anger the German princes

and cities by being seen to bow to the orders of a foreign ruler. It had been

blind obedience to the papacy which had got them into this mess in the first

place. He also must have had in his mind the reaction to Hus' execution. When

word got back that its famous son had gone to the stake, Bohemia rose in revolt

against the Empire. It had taken the better part of a century to end the fighting,

and the Church there had been allowed a considerable degree of autonomy.

So Luther was allowed to leave. Instead, on May 25th, Charles published the

Edict of Worms. Luther was declared a heretic, his works were banned, and he

had the protection of the law removed from him. This was tantamount to a death

sentence.

That is, of course, if he could be found. Luther had already left the Diet,

and on the road back to Wittenberg he had been kidnapped, and had vanished. The

burgeoning Protestant community was distraught. The Lament for Luther

wailed "Oh God, is Luther dead? Who will expound the Scriptures to us as

clearly as he could?"

It turns out, Martin Luther would. Those who had seized him had been agents

of the Elector Frederick of Saxony, his prince and patron. Luther was spirited

away to Wartburg Castle. There, he grew a beard, and went by the name of

Juncker George. Disguised, and safe, he began to work on a German New

Testament. There really was no stopping the Protestant Reformation now.

This was probably inevitable. Unlike earlier heretics, Luther had the major

advantage that he lived after the invention of the printing press. His books

and pamphlets could be made and distributed faster than they could be stopped.

And improving literacy rates meant that more and more people could read them.

Had Charles V ignored his promises, and sent Luther to the stake at Worms, it

probably wouldn't have saved medieval Catholicism. But it would have deprived

history of one of its major thinkers, and one of its more dramatic episodes.

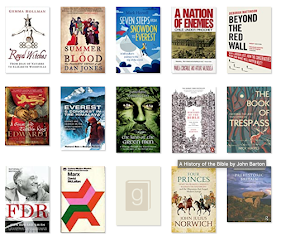

A 19th century rendering of the Diet of Worms