It was the single greatest domestic political blunder made by any postwar UK government. It provoked a huge civil disobedience campaign, violent riots, and toppled the longest-serving Prime Minister of the 20th century, one who won the previous election with a majority of over 100, and had been voted into office by 13.7 million people.

The issue which caused this political earthquake?

Paying for local councils.

No, really.

By the 1970s, Britain's councils were strapped for cash. They used a system called the rates to collect money, based on the potential rental value of a building you owned. It was derived from the system used to collect money for the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601. As councils no longer simply handed out relief to the deserving poor, it wasn't anywhere near enough. More and more money had to be given to local councils from the central government, as costs rose and the value of the rates decreased.

The 1980s were a bleak time for the British left. Labour underwent a near-death experience, as the SDP split and the Bennite revolt came close to destroying the party. The result was two hammering at the ballot box, in 1983 and 1987. At times, the road back to national power looked impossible. But the party did hold power across vast swathes of Britain, at district and county level. It was from here the new left of the 1980s began their fightback against Thatcherism.

Thatcher took notice. Some councils were easy to deal with. The metropolitan county councils, most obviously the GLC of 'Red Ken' Livingstone, were simply abolished. But the costs of other councils continued to spiral as they spent on their new radical agendas. Liverpool council was famously taken over by the Trotskyite Militant Tendency, provoking a showdown with the government and also within the Labour party.

And then Thatcher unveiled her masterstroke of a solution. The rates would be scrapped, and replaced with a 'Community Charge.' A flat rate tax, payable by every adult. The bloc grant from central government would gradually be reduced. After a few years, councils would cover their own costs, and face a grim choice; set higher taxes to maintain levels of service, or set lower taxes to avoid being driven from office. For many, this looked like the end of local authorities as we knew them.

But behind the stunning simplicity were signs of danger. The poll tax (as everyone dubbed the new tax) had repeatedly been rejected by civil servants due to its unfairness; a duke would pay the same as a dustman. It had made its way to Cabinet thanks to over-eager free market advisors who were convinced it would be a vote winner. It would take a test case for the real problems to emerge.

In Scotland, the rates were re-calculated more regularly than they were in England. A rates revaluation in 1985 and 1986 had been politically damaging to the already poor stock of the Scottish Tories. Grasping at any lifelines, the Scottish Conservatives persuaded Thatcher to let them go first with the poll tax. They were so confident that it would be a vote winner that they cast aside the original plan to phase the tax in, and brought it in in one go in 1989.

The problems began mounting soon after. Partly, it was poor administration. A form sent to every household had asked them to list everyone living there- some people filled out everyone, resulting in children and even pets being billed for poll tax. Some people used it as an excuse to disappear from the electoral register. Buildings with an unknown number of occupants, or short term occupancies, proved a nightmare. The other catastrophe was the cost. Far from reducing costs, poll taxes were much higher than rates. Rates had also only been levied on home owners; suddenly, people were getting a bill from their local councils for the first time in their lives, and it was a fortune. But rather than blaming their local authority, the blame rebounded onto Thatcher.

All over the UK, the campaigning left swung into action. The far-left, long on the back foot, was at the centre of the All Britain Anti Poll Tax Federation, which brought together the activities of local Anti Poll Tax Unions. Their opposition was two-fold. The first focussed on protests and marches. This culminated in the huge rally, 200,000 strong, in London against the poll tax, the day before it was brought in for England and Wales, on March 31st 1990. The rally itself passed off peacefully, but after the main march was over it descended into clashes between police and protesters. In what was dubbed the Battle of Trafalgar, protests became riots, and mounted police charged crowds on foot. 339 people were arrested and 113 were seriously injured. The scenes of central London looking like a war zone shocked many. Amongst those condemning the chaos were the Anti Poll Tax Federation itself.

Dramatic as these scenes were, it was the Fed’s other campaigning tactic which was causing the most panic inside the government. Widespread outrage at the way the tax had been handled, plus the spiralling costs, made the Fed’s call for non-payment an attractive proposition. Up to 18 million Britons failed to pay the tax. This refusal was not limited to the ‘usual suspects’ on the far left, but many who had never disobeyed the law in their lives were sending their requests back emoty, or not at all. Such a widespread flouting of the law was unprecedented, and it was this which caused panic in the government. Tory MPs began to get reports of widespread unhappiness with their inability to reign Thatcher in. Labour surged ahead in the polls for the first time in years. The coalition which had kept them in office since 1979 was starting to unravel.

But Thatcher seemed determined to plough on, even as Tory popularity plummeted. She was apparently immune to the panic it was causing amongst her own party. The muttering that the Iron Lady was going rusty were getting louder. Voices began to be raised, opinions shared, that the end was in sight for Mrs Thatcher.

And by an extraordinary twist of fate, the Tory king over the water could claim to be blameless in the poll tax debacle. It had been the next item on the agenda when he had staged his walkout resignation from the cabinet in 1986. When Michael Heseltine made his bid to oust Thatcher in November 1990, he pledged to do away with the poll tax entirely. But that’s a story for another time.

"Hello. In the traditional motion picture story, the villains are usually defeated, the ending is a happy one. I can make no such promise for the picture you are about to watch." (Ronald Reagan)

Monday, 30 March 2020

Wednesday, 18 March 2020

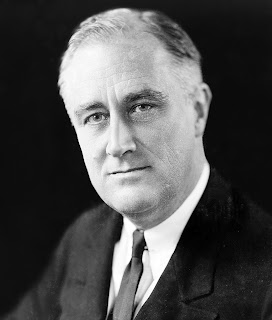

The Wit and Wisdom of... FDR, Mk II

This is preeminently the time to speak the truth, the whole truth, frankly and boldly. Nor need we shrink from honestly facing conditions in our country today. This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper.

So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.

Franklin D Roosevelt, first inaugural address, March 1933. In the words of Mario Cuomo, Roosevelt was the man who "lifted himself from his wheelchair to lift this nation from its knees" during the New Deal.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)